Until Death Do Us Part

- aknowlton

- May 14, 2021

- 15 min read

A plump wild turkey stood alone in the middle of a green field. Plumage fluffed out, face raised skyward. It sunned itself in the rays of a perfect morning.

A happy little turkey.

Then, another movement drew my gaze behind the turkey.

Just then, from the treeline at the far left of the field stalked a large coyote. It's ears drawn back, teeth flashing. The coyote sunk low to the ground; ready for ambush.

Before I could see how the final act would play out we drove out of eyesight. But still I know how it likely ended.

A dead little turkey.

So you found out you are dying.

No, not in the philosophical sense that we're all dying since the day we were born ;gawd I loath that. I mean in the literal- my goose, er turkey, is cooked- sorta terms.

In my experience it's slightly less dramatic and/or climatic then we are taught through life in media.

I learned my fate while admitted to the hospital in a nearby city. I had originally been seen at my local hospital for; what I thought was low hemoglobin (an issue I'd had often in the past that sometime required a couple days stay at the hospital to receive iron and blood transfusions.). While being triaged at my local hospital the ER doc detected something amiss.

He mentioned that my blood volume was low- not quite critically, and also my creatine was high. As a diabetic this happens sometimes. They gave me a high dose of Lasik to get me to pee and mentioned they might transfer me to RVH for further evaluation.

Oookay. I'd had enough varied medical issues at this point to not be too concerned about this development. I assumed that the extra attention was merely cautionary given my expansive medical history.

You know what they say about assuming.

A quick ambulance ride later I was dumped into a over-capacity waiting room with little fanfare. After waiting for approximately four-and a half hours in the ER waiting room, I was brought into the larger hospital assessment rooms. A harried young doctor barked a few cursory questions at me and left the cubicle with nary a word in my direction.

Finally, after what seemed like hours, in reality about 45 minutes, she returned looking preoccupied and less than attentive.

"I don't understand why you came here. Your creatine is elevated, but it's an issue that can be addressed by your family doctor at a later time. Do you know why they (referring to my local hospital ER), transferred you here?"

I blinked at her owlishly. If I knew what they were thinking or what was wrong I'd likely not be here in the first place. So I told her all that I knew.

"All I know is that they said my GFR was reading low and they wanted me evaluated by a nephrologist before being discharged."

At the time I had no idea what a GFR was. I now know that the Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is a test that assess kidney function. Then, I had no idea how serious the earlier test results implied my condition was.

For her part, the doctor looked unmoved.

"I don't think you need to see a specialist at this moment. I think we'll just be discharging you with a note to follow up with your family doctor."

With that, she left me again alone in the cubicle.

After another 45 minutes, she finally returned looking more annoyed than ever.

The head ER doctor had told her to be cautious and admit me for additional blood work. This seemed to annoy her, as she grudgingly brought me back into the waiting room, to wait (some more) while they prepared a room in the ER to send me to.

An hour later I was brought to my ER intake room. In the corner was a soiled bed that looked like someone had possibly been sick in. I sat in the chair in the furthest corner of the room to await someone to come save me. Another hour passed and finally a nurse arrived to take my blood. I showed her the dirty bed when she bid me to go to sleep and explained that I wasn't the patient who soiled it.

I was finally admitted to the city hospital. My room was in the post-surgery recovery unit. My roommate was an incoherent woman with liver failure suffering from alcoholic dementia. My first night, I was give an intravenous blood transfusion and I.V. iron.

I awoke in the middle of the night to my roommate standing beside my hospital bed, staring at me with vacant eyes- lowly growling.

I sat up; because WTF?

I desperately tried to shoo her back to her side of the curtain. I begged, cajoled and spoke as firmly as I could to the creepy stranger that I was forced to share a room with. Nothing worked.

Finally security came to put her back to bed. Unfortunately, the scene repeated itself over and over again. Except one time instead of looming over me, she soiled herself and tried throwing it at me. Another time she accused me of stealing her beer and threatened to attack me.

I was in hell. At 6 a.m. I slept for an hour before being awakened for vitals and breakfast. Exhausted, I assumed this was the worst it would get.

My wicked step-mother-in law and father-in-law visited the hospital under the pretense of visiting me on day two of my hospitalization. Instead they spent two hours in the cafeteria with my husband complaining about my lack of relationship with them. I was tired. Peeved that my husband was being monopolized and annoyed at my Step MIL's lack of consideration.

It was not an auspicious beginning to my day.

Late afternoon my admitting doctor visited me. My overseeing nephrologist stood at my bedside and delivered the Earth shattering news; his face and tone utterly neutral.

Both kidneys were in failure. My body was dying. I needed to start dialysis soon. There was no chance at improvement. Dialysis would stabilize me, but my best chance at long-term survival was a transplant.

Fuck.

It was not easy information to digest. I didn't know much about kidney disease or what exactly the doctor was saying as his voice faded and the timing pressure in my ears built. I heard the words end-stage and I knew.

I'm dying.

The thing about death and mortality is that, even though everyone of us will each inevitably die; we as a society live in a perpetual state of denial about death. It's treated like a dark family secret. A proverbial skeleton in the closet. Taboo.

Stating simply to another person, "I'm dying," will garner, without fail- awkward, averted gazes, denial and empty platitudes. Worse, treat your advanced mortality with humour and many of those around you will recoil in horror. We are trained from a young age to avoid the topics of death and dying. Treat it like some mystical secret, a tainted topic too risque for tender ears.

The reality is that death is universal. It comes for us all- human, animal, insect and plant. Although it is unknown and mysterious, it is a certainty.

Death and I have become close friends over the years. I've lost too many people in my life, too soon. However, the most profound brush with death came six-years ago.

At the time my husband Andrew and I were almost six-months pregnant with a son. On June 14th we were told our most recent bloodworm indicated an issue. We were sent to Mount Saini in Toronto to see thier genetics and high-risk pregnancy department. Our tests revealed major medical issues with the fetus. Our baby didn't have a chance at a normal life. If he survived birth at all, he'd live less than a week and be in constant pain. I won't get into what was wrong- no one needs to hear that nightmare.

We left the city with instructions; we needed to choose our baby's fate. Carry to term or terminate. The longer we waited the greater the risk to myself as mother, and the greater the potential suffering of my baby.

Then on June 19th we received the call from Mount Saini, asking for our decision. I had talked with my family; sat with my father and got his advice.

We set the date for termination: June 21. I wanted the day of my father's birthday to just be about him.

I have always been a daddy's girl.

My dad was my best friend, my hero and my biggest fan.

Robert Glenford Knowlton was biologically my maternal grandfather. But not-knowing anything about my birth father as a child, and living with my maternal grandparents from birth; naturally I sought a father figure. At age two I asked my grandpa: "can I call you daddy?"

He was happy to fill the role.

He became my best friend, my protector and my inspiration.

In early fall 2014, my father was diagnosed with stage-4 esophagus cancer. He was given 4-6 months to live.

My father has always been terrified of death. It was a family inside joke; how he'd get grumpy the few days leading up to his birthday. Then on his birthday June 20, 2015- it seemed we found out why.

The day began like any other. Except for this time my dad was more lucid then he had been in weeks. I made him a rye and coke at his behest and sat with him and talked. He held my hand and told me he loved me.

A few hours later, he slipped into a catatonic state.

No longer lucid he slipped away from me. His eyes starring and unseeing, he entered the final stage before death took him forever away. I wanted to run. I didn't want to witness my daddy's final good-bye, but I could not leave him.

I held his hand. I whispered, "I'm here daddy. I love you. I'll always love you. It's okay to let go. I'm going to be ok." Over and over again.

"I love you. I love you. I love you."

I listened to his shallow breathing become a rattle. The gurgling-gasp of a dying person is a sound you never forget.

And then silence.

One second he was here....the next, just...gone.

I looked to his body and though it was the same as it had been a few minutes before, it was also suddenly entirely different. It was lacking him. He was gone forever.

I broke. I sobbed. I clutched at his night shirt and bawled.

I've never felt so alone. So utterly alone.

After I spent my final minutes with him, the time came to call the funeral home.

Our former house was not set-up with disability needs or ease of physical transportation in mind. A tight split landing- barely big enough for a single person, gave way to a steep curved staircase to the main floor where my dad rested in his bedroom.

When the funerary attendants arrived, I stared in disbelief. The first man was tall and willowy. More gaunt then appeared healthy. His partner was tiny. Frail and elderly. Both were sweet-but a more mismatched pair, I could not have conjured if I had tried.

My father was not a small man. In his day he was over six-foot tall and 260 lbs. Even after being ravaged by cancer he was still an imposing figure.

The two attendants struggled to get the gurney up the stairs- knocking it into the railing, the steps and gauging chunks out of the wall in the process.

I was not confident this would end well.

The men entered his room to prepare his body for transport and get it in the body bag they had brought with them.

After a considerable lapse in time, and listening to what can only be described as a vaudeville comedy act going on behind the closed door, I offered them my assistance.

Both demurred my offer, assuring me that they had it well in hand. Moments later they emerged from the room with the gurney. Laying atop the stretcher was my father's body, contained with the thick black plastic bag.

The sight caused my heart to stutter and fresh tears to burn in my eyes.

As I felt my grip on my emotions slowly slip from my control, the duo breached the threshold of the staircase.

The taller of the two went first, rightly putting himself in the position to bear the most of the weight himself. The smaller man took point at the aft-end; attempting to hoist the contraption into the air and pivot it, in order to negotiate the tight curve of the stairwell.

The poor little elderly man was shaking under the weight of the gurney loaded with my father. He was attempting to deadlift it up and presumably over his head when his arms gave way. The gurney and dad came crashing to the floor with a thunderous boom.

The room fell silent. Everyone blinked at each other. Then from the body bag emitted a familiar sound.

Pffffffttttt.

The smell of fart and human soil spilled through the room.

My stoney face broke. And I laughed. Like a hyena. Until tears streamed down my face and I gasped for breath.

The poor funerary assistants looked distressed.

"Relax gentlemen. My dad would have had a great chuckle over this. I'd have his send-off no other way." I told them as I wiped at my tears.

Visibly relieved the men got to work again. This time I took point at my father's foot and hoisted him up with all my might. Between the three of us we were able to get him down and around the stairs and through the front door.

He was loaded in the Hearst and I watched him drive away for the last time. Standing in my driveway, watching those lights faraway, I've never felt less secure in the world.

A day later Andrew and I were in Toronto checking into Mount Sinai hospital. We'd made the difficult decision to terminate our pregnancy, knowing or son would only live a few days at most- and be in immense pain through all his brief life. Still numb from the loss of my dad, I was sleep walking through the day.

Late-term abortion is not as uncomplicated as early-term. In our case it was a two-day procedure. The first day we were there they had to complete a procedure that would stimulate cervical dilation.

The pain of the contractions I felt that night was punctuated by the cruel fact that at the end of the process, I would not be holding a hale and hearty son, but leaving mourning his death.

Months later, Andrew and I finally took a long-overdue honeymoon. Our first (weak) attempt at a long-weekend away was cut short before the end of the first night when my mother fell and shattered her arm. It took months for her to heal, and by the time she did, dad was sick and I had no desire to be any distance from home.

Life has a strange way of working out for the better.

In October 2015, we had finally saved up enough to take a real vacation. We booked a five-star adults only all-inclusive in the Riviera Maya. We toured, relaxed and had the most alone-time we'd ever had together.

The day before we were set to leave, October 29th (the locals were getting ready for their Day of the Dead), we finally made it to the market in nearby Playa Del Carmen. I was determined to find a unique memento of our trip.

After finding a cool boutique that sold original tattooed leatherwork by local prisoners (proceeds benefited thier families), I was excited to have my unique souvenir.

Andrew was a little easier to please. All he wanted to get was a ceramic sugar skull. Now, if you've been to Mexico, you know these things are everywhere. So on our way back we passed a small booth not unlike any of the dozens of others on the strip.

Andrew found a few he liked and was haggling away with the vendor- bored I wandered off to check out the rest of his wares. Tucked away at the back of the shop was a small Day of the Dead statue of a pregnant woman. As always, at the back of my mind I was thinking about the baby we lost not long ago.

I'd never seen one like it at any of the other booths and somehow it felt like it was put there for me. The vendor gave it me for a single American dollar. The simple statue became one of my favorite things. It became a way for me to integrate the loss of my baby into my home environment and to find beauty in his memory.

Finding a way to integrate the reality of death is key to finding a way to live with it. In my opinion the manner of integration will be as unique as a fingerprint for each individual. For me, I'm most comfortable when I'm in charge, when I'm planning and organizing.

So my first-step was taking charge of my mortality. Instead of dancing around the reality, I took to being frank; "I'm dying." It was a statement I got used to. From the very beginning of my diagnosis, people seemed fixated with the question: "How long do you have?"

Most people were not quite forthright with the question. Many danced around it. And perhaps most frustrating of all was how the medical professionals approached the question. It was obvious that they were trying to deliver the news that my time was limited. However, I got the impression that while they were hesitant to flat out say: "you're dying;" that was in reality the exact message that they were trying to impart.

What really irked me was that everytime I pressed for an approximate expiration date, my doctor's did their best to dodge the question. This I understood intellectually. There was too much room for error, too many possibilities. But as the patient, learning to live in that new reality- it felt like a sick joke.

So me being the low-key control freak that I am, I threw myself into learning everything about the morbidity and fatality demographics of EKD.

You know what they say; ignorance is bliss.

Arming myself with a full understanding of my disease helped me understand what was happening to me. It also gave me new fears and anxiety.

At one point my anxiety about my shortened life-span got so profound, that in desperation I sought advice through the realm of the self-help book. Most of the books I reviewed (none did I read to completion) were of little use, all were written by "experts" who have never been terminally ill, some of whom profess second-hand experience. These titles mostly just frustrated and enraged me.

One book, The Art of Dying by Patricia Weenolsen was more informative and helpful than the others. But still it lacked something that only another person who walks hand-in-hand with the Grim Reaper can give. This is what inspired me to write my own blog.

When I faced uncertainty about my mortality after my heart attack, I turned to music. In the evening and hours before I went in to my open heart surgery the only thing that calmed me was listening to my playlist.

Not surprisingly, one of my go-to calming methods is listening to music. Morbidly, I have two main playlists on my Spotify:

1) music about dying

2) music for my lived ones to hear after I die.

Although my About Dying playlist, sounds depressing; it's actually full of uplifting and inspirational songs. Some of my dying jams are actually really upbeat. Like the song Odds Are by BNL or I Wanna Get Better by Bleachers. And also there are softer ones. Like The Night We Met by Lord Huron, Let me Hold You by Josh Krajick or Autumn Leaves by Ed Sheeran. And because we all need to cry sometimes, I have a couple songs that sure to bring on my tears.

My playlist that is curated for After I'm Gone has been created with the intention of speaking for me to my loved ones, when I no longer can, like How Long Will I Love You by Ellie Goulding. It's there to allow me to continue to affirm my love for them, my hopes and dreams for them and to thank them for all the gifts they bestowed upon me.

I've noted some songs along the way that would be appropriate for my Celebration of Life or Memorial service.

I have also began working on my regalia again. I chose a jingle dress, because I felt drawn to the teachings that tell how the jingle.dress was given to the Anishinabek as way to heal it's people.

The story goes that a Medicine Man from Whitefish Bay in Ontario had a gravely ill daughter. He prayed and meditated on her illness to the Creator, who sent him visions of a sacred healing dress.

He dreamed of a healing dance.

And so he spent days making the dress from his dreams. When he was finished he put it on his daughter and lifted her so she could dance. As she danced, she got better.

I hope that I can get better too. I dreamed of my colours. I am making my dress. I'll wear it to Pow Wow. And if creator calls me home, I will wear it to meet him/her again.

I've found that planning things like that reduced my anxiety and helps put me at ease with my mortality.

Taking charge has become my best coping mechanism. It keeps me sane and actually gives me purpose. Without doing do, I find myself at times getting paralyzed under the weight of my uncertain future.

Aside from the superficial coping mechanisms, I have also been slowly tackling the more pragmatic tasks associated with my early death.

I'm updating and ensuring my will and power of attorney is reflective of my unique needs. As part of this process I am also clearing up long-standing custodial issues leftover from my first marriage.

Another task I'm finally getting around to is plugging away at obtaining my Indian Status. Personal hang-ups regarding my later-in-life discovery of my paternity, had made me drag my feet in that department. Now I realize that I've done myself and my kids a disservice by doing so.

I've also begun to preplan my funerary arrangements. Knowing my husband as I do, leaving it to be dumped in his lap immediately after I'm gone is cruel. If I send Andrew to the grocery store, he wants a comprehensive list detailing exactly what I am sending him for. He doesn't like being left with room for interpretation.

Instead of bogging Andrew down with the responsibility of choosing every aspect of my last arrangements on his own, during what is sure to be one of the most emotional moments of his life, I have set clear directions for him to follow.

To begin with, we have had numerous frank and open conversations. How we envision commemorating my passing, if he or I prefer cremation or burial. These conversations are based in practical terms ( e.g. our economic circumstances) and in our own personal ethos; for example my own views on environmental impact of conventional burials.

I've begun researching the procedures needed to file claims on my life insurance policies. And re-establishing appropriate powers of attorney.

From making rough plans to researching options and calculating costs with local funeral homes. It's been a jouney of discovery.

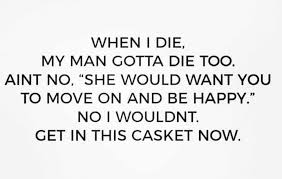

Andrew and I have had the hard talks, the real talks and funny talks. I jokingly told him that he wasn't allowed to re-marry and instead I expected him to crawl into my casket and come with me.

By joking about these issues, we opened the door to discuss potential terms for what will come after. Things like how long before a new potential partner is exposed to the kids, what to do with my cremains if said partner is uncomfortable with my cremains being on "display" in the home.

I'm not keen on being put in a closet and forgotten, but I understand another woman not being excited about my mortal remains gathering dust on thier mantle. Andrew and I have talked about it all. Even though I know that circumstances will effect the actual outcomes in the future, I am content knowing that we've at least had these discussions. Not exactly closure; I don't think I actually believe in such a thing, but I have given my informed input. And I know it has been heard. Maybe that's better than closure. Just like in life, in death nothing ever really ends.

Angie I am a big fan of your writing. As soon as the notification pops up that you have posted I drop everything and read it. Truly amazing work!